Docker is renowned worldwide as an open-source container service provider, that excels in packaging applications and their components, along with dependencies, simplifying the deployment process. It is a powerful and versatile tool, that streamlines the creation, running, and management of software applications. However, before we delve into Docker’s inner workings, let’s start by grasping the fundamental concept of containers.

Understanding Containers: 🔗

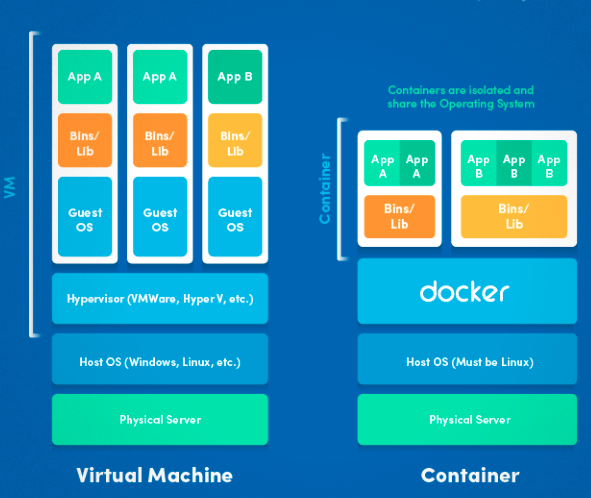

Containers are much like virtual machines, but while virtual machines simulate an entire computer, containers create a sandboxed environment that imitates a virtual machine. These containers typically run the most streamlined version of the required software and professionals often construct stripped-down operating systems that excel in performing a single specialized task.

Docker is the tool that facilitates the creation and execution of these containers, allowing you to save them as templates for future use.

Docker’s Three Key Components: 🔗

🏭 Imagine Docker as a well-structured factory with three critical elements:

-

Docker Client (👨💼 Manager): Picture yourself as the manager. In this role, you give instructions to the Docker Client, much like a manager directing the factory’s operations.

-

Docker Host (🏭 Factory Floor): The Docker Host represents the factory floor where all the work unfolds. It diligently adheres to your directives, similar to how factory workers follow a manager’s lead. The Docker Host manages various aspects, including images (🖼️ like blueprints for products), containers (📦 the actual products), networks (🔗 internal connections within the factory), and volumes (📦 storage for materials).

-

Docker Registry (🏬 Warehouse): The Docker Registry serves as a warehouse where you stockpile your blueprints (🖼️ images). Docker Hub is a colossal, publicly accessible warehouse containing an array of blueprints that anyone can utilize.

How Containers Work in Practice: 🔗

Imagine you have two containers running – one hosting a Redis server and the other an ArangoDB instance. Each container is based on pre-built templates, and you can start them with minimal configuration. Importantly, these containers only expose the necessary ports to perform their tasks, making it challenging for hackers to access them like a regular computer.

Docker’s Versatility: 🔗

When it’s time to deploy your application to production, Docker streamlines the process. You save your containers as image files and deploy them to your chosen server instances, whether it’s on Amazon, Google Cloud, or elsewhere. Docker abstracts the underlying operating system, ensuring your containers run consistently regardless of the host’s OS.

Unlike virtual machines, Docker’s lightweight containers have minimal performance overhead, ensuring efficiency.

Docker Files: 🔗

A Dockerfile is a simple instruction file that tells Docker to download an image and execute commands on it. These commands may include installing additional software or configuring the environment to meet your application’s specific needs.

Now, let’s explore how Docker functions when you want to run a container, build a custom image, or pull an existing image in this factory:

Building a Custom Image (“🔧 docker build”): 🔗

With docker build you take on the role of a designer creating a completely new product from scratch. You provide precise instructions in the form of a Dockerfile, similar to providing detailed specifications for the product’s design.

The factory (Docker Host) diligently follows your instructions, crafting a unique product that adheres to your specifications. Once the custom image is constructed, it becomes a brand-new product ready for use within the factory.

Pulling an Existing Image (“🚚 docker pull”): 🔗

In the context of docker pull you venture to the warehouse (Docker Registry) to acquire a pre-designed blueprint (🖼️ image) produced by someone else. You fetch the blueprint (image) from the warehouse and transport it into your factory, where it is stored for future use. It’s like to purchasing a product design from a supplier and maintaining it within your factory, available for future production.

Running a Container (“🏃♂️ docker run”): 🔗

You, the manager, initiate a docker run command, much like issuing an order for a new product within the factory. Docker, acting as the factory, procures the required blueprint (🖼️ image) from the warehouse (Docker Registry), like retrieving a design for the product you wish to create. Docker proceeds to fabricate a brand-new product (📦 container) based on that blueprint.

Subsequently, Docker allocates a designated workspace for the container, similar to setting up a workstation (🧰 filesystem) for product assembly or customization. Docker connects the container to the factory’s internal systems (🔌 network interface), enabling it to interact seamlessly within the factory. Finally, Docker activates the container, and your new product is up and running within the factory, ready for use or further customization.

Conclusion 🔗

In summary, Docker simplifies software application management by creating isolated containers. These containers can run on various hosts, regardless of the underlying operating system. This flexibility, along with Docker’s efficiency, makes it a game-changer in technology.

If you liked this article, go follow me on Twitter (where I share my tech journey) daily, connect with me on LinkedIn, check out my IG, and make sure to subscribe to my Youtube channel for more amazing content!!